1.2 Preface

Chibli Mallat

Introduction

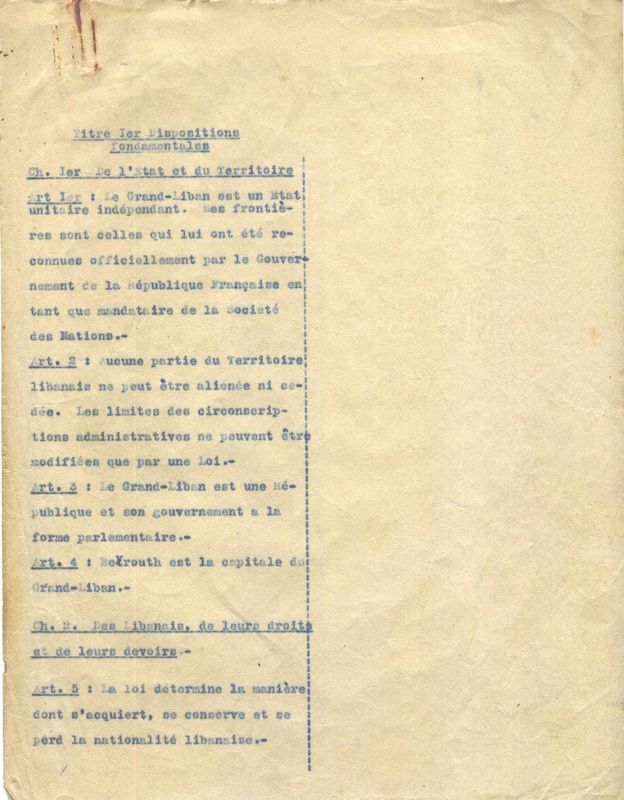

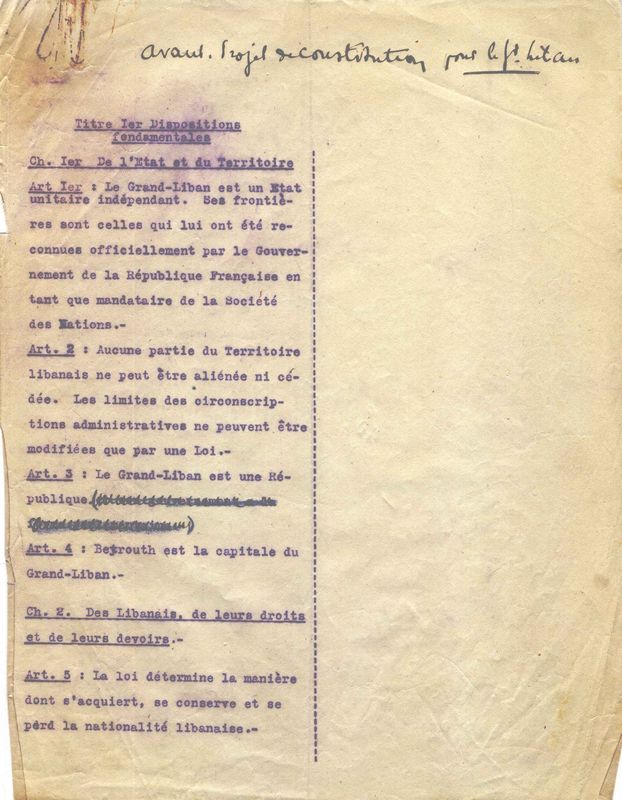

This book is a companion to my Democracy Redefined: Michel Chiha and the Lebanese Constitution (MCLC). It also stands alone. The documents represent the full facsimile set of Michel Chiha’s Constitutional Papers (CCP), from December 1925, when he started working on the draft, to late May 1926 when the Lebanese Constitution was adopted by the members of the Council of Representatives. Thanks to the Chiha Foundation, a unique archive of papers on the Lebanese Constitution is now available to a wide public.

The reader will find in MCLC an extensive analysis of the Constitution in historical and comparative perspective. Typical of the Middle East, Lebanon’s communal (or communitarian) straitjacket ties citizenship to a communal/religious/sectarian identity which is at the heart of the difficulties faced by a majoritarian democracy in shaping the nation-state. MCLC explores this tension and its meaning for constitutionalism and the theory of democracy.

Here is a summary of the book.

The introductory chapter provides an orientation to religion-based communalism in linguistic/historical categories and sketches present-day Lebanon’s institutional history and the materials used for the book. It is followed in the first part of the book by an investigation of representative councils in the Levant since Napoleon, and in Lebanon as a unique terrain of constitutional experimentation, together with the slow adoption of the principle of elections in the regime of the Mutasarrifiyya (1860–1920) and the wider Ottoman Empire. This first part enlightens the Lebanese Constitution as we know it today, derived from the long march of Lebanese and Middle Eastern legal institution-building, with the first communal governing council dating back to the majlis al-mashura (or majlis al-shura) in 1834 Beirut. The charter of the Majlis designates as members ‘six Muslims and six Christians’. The Lebanese Parliament, almost two hundred years later must still, under the Constitution, be composed of Muslims and Christians ‘on a parity basis’. As for elections, even the earliest choices of official representatives in Lebanon, both in Beirut and in the Mountain, were based since the second half of the 19th century, on their religious community or sect.

The second part is devoted to the life and tribulations of the Lebanese Constitution, the oldest surviving constitution in the Middle East and a testament to the talent and foresight of Michel Chiha (1891–1954) — pronounced /Shee-haa/ (with a strong h, transliteration Shīḥā). Chiha was a respected liberal thinker of the 20th century who wrote its first drafts in French. The CCP allow an unprecedented and unique window on the drafting of the constitution in the first months of 1926 through to its adoption at the end of May. The reader of the CCP can follow the genesis of the Constitution over six months of a rich tapestry of drafts and versions under the control of Chiha, and the input of other Lebanese contributors as well as the French Mandatory power. MCLC reconstructs the genesis of the Lebanese Constitution with the help of existing scholarship, the CCP, the contributions of the ‘Founding Fathers’, and contemporaneous daily press coverage. The composition of the Constitution’s articles is enlightened in the continuous debates culminating in the article-by-article deliberations in the Council of Representatives over the last four days before its adoption on 23 May 1926.

In the third part, MCLC paints an intellectual portrait of Chiha through his many writings and public positions. Although Chiha did not leave us a full book of reference either for his role in writing the Lebanese Constitution, or of his worldview, his written legacy, published in eight volumes and now enriched by hundreds of articles made available on the Chiha Foundation site, expresses a liberal view for Lebanon which is careful in dealing with its religious groups. Some of his most alluring texts provide a reading of Lebanese history. Others offer a broad range of far and wide, opinions on the rise of Nazism in Europe to views on the Second World War and the Palestinian tragedy of 1948.

The communal concerns which characterize the Lebanese Constitution provide the background of the fourth part of the book, which addresses two conflictual views of democracy: one is traditional, individual/Kantian, the other is communal/Chiha and is typical of the Middle East and lies at the heart of its troubled history. Through a comparison with Middle Eastern constitutionalism, then within a larger framework of political theory, a new conceptual framework for democracy is proposed. It is based on group representation in government that considers citizens as members of historically subordinate groups. A taxonomy of subordinate groups is presented on the basis of trait immutability, and in terms of group entry and exit, leading to a theory of Democracy which rests on the necessary representation in government of individuals-in-a-historically-subordinate-group, and the wider political and constitutional concern with the tension occasioned by the majoritarian view of democracy and the recognition and effectiveness of ‘discrete and insular groups.’ By setting the Lebanese example against the wider Middle Eastern and planetary applications, MCLC raises critical questions about the democratic structure of government and proposes markers for its redefinition.

Scholars will no doubt refine, enrich, build on, improve, even contradict various issues of importance adumbrated in MCLC. Access to primary sources will make their efforts easier. An essential part of the record analyzed relies on the constitutional papers in the Chiha archive. They are provided here to stimulate discussion and research, and allow lawyers, historians, political scientists, politicians and citizens at large to visit the Lebanese Constitution as it enters its second century with a rich, unprecedented documentation. The reader has now in their hands a full and unique set of historic documents exactly as they survive in the Chiha archive.

This is also an eye-catching book which keeps color and size of the original texts intact. In good part because of Chiha’s neat and stylish handwriting, readers can travel to the foundations of a legal monument which survives to endure in a new century. They will see for themselves what the documents say and how they came together in the making of one of the few constitutions still in force on the global scene. They can now appreciate through key original documents if and how the Lebanese Constitution elicits a unique challenge to democracy in the world and its corresponding constitutional design. This preface is duplicated in the Arabic version of this book and raises some issues of particular interest to the young reader. The French preface is different and raises more complex constitutional issues.

As time passes, the rule of law as defined by the Lebanese Constitution becomes more firmly anchored in the Lebanese citizen’s imagination, if not in the Lebanese practice of politics. I am pleased that publication of this volume will coincide with the first centenary of the Lebanese Constitution. A better understanding and a richer use of the Constitution are needed now more than ever.

Chibli Mallat

Beirut, May 2025

![Titre 1er Dispositions fondamentales (manuscript, in Michel Chiha ['MC']'s handwriting) 85 arts., 15pp.](https://ujw7dc7s7zbfowlxtjls6losoe0soyej.lambda-url.eu-central-1.on.aws/iiif/3/01/01/full/!800,800/0/default.jpg)